In hopes of sparking renewed commitment to applying improvement science to telehealth, we offer this Telehealth QI and QA Miniseries. Today is the fourth in the series.

Require expertise and excellence in telehealth service delivery. Expertise with telehealth requires deliberate practice which builds on or modifies existing skills, usually with the help and guidance of a coach or teacher with targeted feedback on what to improve and how to improve those skills.

- Send staff through telehealth training either internally or externally. The California Telehealth Resource Center Telehealth Course Finder is a great place to start for external telehealth trainings.

- Provide peer review of telehealth sessions by inviting a trusted clinician to join a telehealth visit – with patient permission. Debrief after the session to provide feedback and to discuss what went well, what did not go well and what changes can be made to improve

Implement written triage protocols that are easily accessible by all staff to clarify which patients or patient issues are appropriate for telehealth and which need to be seen in person.

Make a commitment to exceptional service delivery.

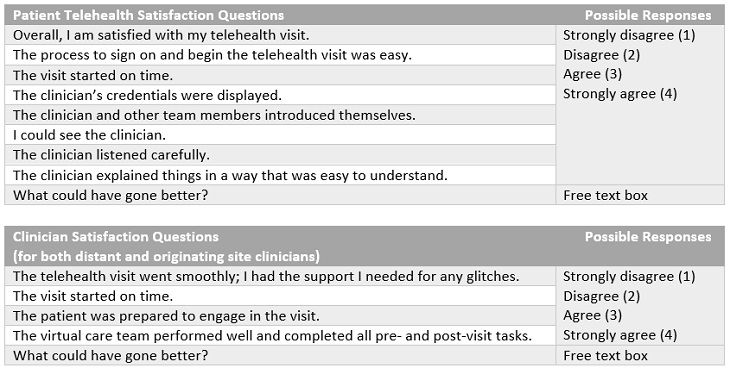

- Solicit and act on patient and staff feedback. Consider including a patient partner or advisor in these efforts. Below are some sample staff and clinician satisfaction survey questions. Some institutions may already incorporate some of these into their existing patient feedback systems (e.g., Press Ganey) so check to see if they are before duplicating efforts. Sometimes it’s best to collect feedback simply and in real time by asking, “How was your visit? What could have gone better?”

Recognize that emotional and mood cues may be missed. Because the communication is different with telehealth or calls and may not include a video component, facial cues are blunted, and clinicians may not see distress or tears if not using video. Audio cues (e.g., voice tremors) may not be as obvious as during an in-person visit, body language (e.g., tapping fingers, wringing hands) if often not visible, and even smells (e.g., whether or not a patient has showered recently, smells of tobacco or marijuana) are absent, increasing the need for providers to pay more careful attention during sessions and ask probing questions.

Plan for emergencies. In addition to having the patient’s phone number if connectivity fails, it is important to have this information in case of an emergency. It is also important to tell the patient what the procedure is if the connection fails (e.g., will switch to phone and provider will call patient).

Know the physical location/address where the patient is. If emergency medical services need to be called for the patient, it is a key aspect of patient safety to know and document the specific location of the patient. Additionally, just planning to call 911 may not suffice. Always have on hand the emergency phone numbers in that patient’s location/county (e.g., staff may need to call the Sheriff’s Department directly) as well as local (to the patient) mental health crisis lines.

Protect the privacy and security of patients protected health information (PHI). Use headsets so everyone within earshot cannot hear the conversations and suggest/provide headsets or ear buds for patients when needed. Always use a HIPAA-compliant telehealth platform. Adhere to all other provisions of the HIPAA Privacy and Security rules. Always know who is in the room with the patient and let them know if anyone is in the room with you.

If we don’t commit to ensuring that telehealth is a good experience for everyone involved, our telehealth gains will not be sustained.

Use the SWTRC Contact Us form to share your telehealth measures and/or experiences with telehealth quality improvement.